|

The Psychedelic Vision at the Turn of the Millennium:

Discussion with Andrew Weil, M.D.

The following is exerpted from the pre-conference of the 1997 Association

for Transpersonal Psychology Conference held at Asilomar Conference Center

- Monterey, California; August 1-3, 1997.

The pre-conference was entitled

"The Psychedelic Vision at the Turn of the Millennium." The featured

speakers were Charles Grob, M.D., Laura Huxley, Dennis McKenna, Ph.D.,

Terence McKenna, Ralph Metzner, PH.D. and Andrew Weil, M.D.

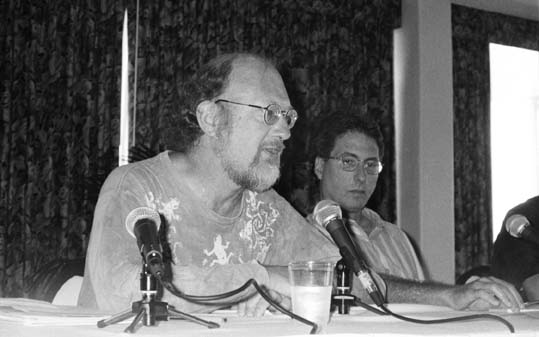

(pictured here from the left: Dennis McKenna, Charles Grob, Andrew Weil, Laura Huxley)

C. Grob: It is my pleasure to welcome you to the morning session of The

Psychedelic Vision at the Turn of the Millennium.

I would like to introduce our first peaker of the morning, Dr. Andrew

Weil, well known to many of you. He has become an extremely successful and

well-known speaker on the topic of alternative medicine. He has had a

number of books recently achieve best-selling status, including

Spontaneous Healing and Eight Weeks to Optimum Health. His message that

modern medicine needs to avail itself of resources previously ignored,

including the medicines from the plant kingdom and alternative models to

understanding healing and prevention, have now achieved far greater

visibility and respect not only within the population in general but

within the mainstream profession itself.

Andy has recently developed a new and innovative program at the University

of Arizona School of Medicine; a training program, training physicians in

alternative medicine, theory and practice. The center there is called the

Program for Integrative Medicine and it is really a pioneering program in

the training of physicians in alternative models for healing. Andy is a

clinical professor of Internal Medicine at Arizona. In addition to his

recent activities being very visible in the alternative medicine movement,

Andy also has a rich history, going back some years, looking at the

phenomena of altered states of consciousness and particularly substances

that might induce such altered states. In addition to his very important

early works, The Natural Mind and The Marriage of the Sun and the Moon,

written some twenty-five years ago on these phenomena, Andy also was

present in the early days at Harvard University, where psychedelics first

became an issue in the public domain and in fact, was a reporter then, I

believe an editor for the Harvard Crimson, breaking the story to the

Harvard community and the world.

So, Andy is with us today, having gone through a tremendous odyssey over

the years, and is still quite willing and quite happy to talk about his

early interest, which I believe is still an active interest. I give you

Andy Weil.

A.Weil: Good morning. Laura [Huxley] has offered to sit next to me for

moral support. I will tell her--I told her this once--I will remind you

again of my indebtedness to Aldous for my early experiments. I read The

Doors of Perception in the summer of 1960 and then in that fall I entered

Harvard as a freshman and was very eager to try mescaline as a result of

reading that book. I had no idea, I had never heard of these substances,

I had no experiences of any psychoactive substance other than alcohol, and

in my na•vetˇ, the first thing I did was go to my corner druggist and ask

if he knew where I could get mescaline. He said that he had heard that

there were experiments going on of trying to reproduce schizophrenia in

the laboratory but he had no idea where you could get it. And I remember,

I talked to several people, I asked my family doctor. I made the mistake

of talking about it at the dinner table one night, and I saw the reactions

it produced in my parents so I said nothing further. And then by

coincidence that Fall, Aldous was at MIT as a visiting professor and gave

a series of lectures, I think four lectures on visionary experience, which

were broadcast on the Harvard radio station on Saturday afternoons. I

listened to them entranced, those lectures that later became, I believe,

Heaven and Hell, is that correct?

L. Huxley: No, I think that those lectures are part of a book called, The

Human Situation.

A. Weil: Well, they were very inspiring so I wrote a letter to Aldous

Huxley. I think I sent it to him in care of MIT and he sent a handwritten

letter back, giving me the name of a chemical company that he thought

would sell mescaline. This was called Delta Chemical in New York. I wrote

them a letter, this was in the pre-Thalidomide days when there was not

very much checking about who got what and they would indeed sell

mescaline, but at about five times the price that it should be selling

for, with no questions asked. I then heard that there was a professor

named Leary who was interested in these substances. So I went over to see

him and he said that he was sorry that I couldn't be in their experiments

because he couldn't use undergraduates, but he said I should just keep

checking and I could probably find it. I think I wrote back to Delta

Chemicals and said, did they know anyone else who manufactured mescaline,

and they gave me the names of three companies and they sent out these

forms that were fairly simple to fill out for using the drugs for

investigational use. I mean this was in the innocent days and I found one

of these companies that was willing to sell mescaline and developed a nice

relationship with them. It would arrive by UPS outside my dormitory,

twenty-four hours after I ordered it. So, I am very indebted to Aldous for

the lead. The first time I tried it, I tried it with one other friend of

mine, and there was a group of people in my freshman dorm who were

interested in it, but everybody was quite scared. I and this other fellow

had volunteered to try it first. It was not an ideal setting, with the two

of us taking it with a whole group of people sitting around, waiting to

see what would happen. It was on a Saturday afternoon and my set was so

filled with anxiety that it was about three or four hours before I felt

anything at all. When I did feel something, at the beginning it felt like

alcohol intoxication; that was really the only model I had for what an

altered state was like. At the moment I started to feel something the

phone rang, and it was my mother calling from Philadelphia, who never

called on Saturdays. I mean it was an awkward conversation. She asked me

about the weather and I said it was nice and she said, "Why aren't you

outside," and, "What are you doing?" and I said I was just sitting around

with some friends. She said, "I hope you are not doing anything foolish

like taking mescaline." I had mentioned the word once about two months

before. Mothers...

I SAID THAT I would talk to you about practicalities and my interest is,

"Okay, you have seen the psychedelic vision and you know, now--what do you

do with it?" You can see it over and over if you like, but it seems to me

the challenge is how do you trans-late it and what do you do with it.

There are a lot of people in our culture who have had this vision now, and

our concern is how is this going to be implemented. What can we do about

it.

So again, I will talk very personally about this. Let me begin by just

giving you some of the key elements of the particular vision that I

experienced as a result of psychedelic experimentation. The first, I

think, is a sense of wonder, of just wonder and awe at the universe, at

life, at consciousness. While that may seem simple, one of the things that

has been very disappointing to me and striking in my career in medicine

and the sciences, is the absence of that feeling on the part of many, if

not most of my colleagues and I find that very dismaying. In fact, I even

detect a strong feeling among some of the hard core scientists that I went

up against, that it is the business of science to do away with wonder.

That science is seen as being able to roll back the mystery. I remember

hearing Terence once say, he used an image which is terrific, that the

bigger you build a fire and the more illumination it gives off, the more

it makes you aware of the extent of the darkness beyond. I think that is

very true, that fits with my experience and I think that is very much at

odds with the scientific view, that the business of science is to do away

with mystery. It seems to me that mystery is at the heart of existence and

it is something that one experiences very profoundly as part of the

psychedelic vision, whether it is the heavenly vision or the hellish

vision. That has always been a very motivating force in my life. I think

it has also kept alive my sense of curiosity. I am a very curious person

and I check things out and I do it with this sense of wonder and it seems

to me that is a very healthy attitude to have. Especially very healthy as

a scientist and as a physician. So, I have always tried to inspire that in

people that I come into contact with, and in medical students, but I am

very aware that I am up against a tremendous force in the opposite

direction. It seems to me that is one thing that I try always to counter

in my teaching, that comes directly from that psychedelic vision.

Another aspect of the psychedelic vision, for me, was the sense that

anything is possible. That although there may be relative limits in the

here and now, in some higher sense, there are no limits, that we live in a

universe and that infinity and endless possibility are there. And again, I

emphasize that this is a contrast because I think we live simultaneously

in the three dimensional world where limitation exists and in some higher

dimensional reality where it doesn't, so there is paradox there.

I will give you a very practical story about my experience of no limits. I

wrote it down in a book that Lester Grinspoon edited on the psychedelic

experience, but I will just repeat this for you because it has been for me

a very meaningful model and one that has, again, motivated me in my work.

This incident took place about 1970. I was living in rural Virginia, it

was at the time that I was getting ready to write The Natural Mind and it

was a period of great transition, when I had quit a government job and

dropped out of medicine and was starting to meditate and do yoga and

became a vegetarian. It was a time of great change in my life. Also, the

political times in those days were both scary and very optimistic. One day

in the spring of that year I took LSD with a group of friends, it was a

perfect spring day and I was just in a wonderful state. I had been trying

to start Hatha Yoga, as of a couple of months, and I had a lot of

difficulty with some of the postures. The posture that I had the most

difficulty with was the Plow, where you lie on your back and try to bend

your feet down behind your head and touch the ground. I could get them

down to about a foot from the ground and I would feel an excruciating pain

in my neck. There was no progress at this, I had worked at it for about

two months and I was on the point of giving up. I was twenty-eight, I

decided I was too old and that my body was just out of shape and wasn't

made for this. Well, in this LSD state I was just feeling so happy. I

observed that my body felt completely elastic and springing and I thought,

"Well gee, while I'm this way I ought to try doing the Plow." So I

lay down and I was lowering my feet behind my head and I thought I had about

a foot to go and they touched the ground. I couldn't believe it! And I kept

raising them and lowering them and it was just, it was fabulous. The next

day I tried to do it and I could get my toes to within a foot of the ground

and there was excruciating pain in my neck, but there was a difference now.

The difference was that I had seen that it was possible. And I don't think

I would have believed that, I was on the point of giving up.

That experience of seeing that it was possible, even though it had now

disappeared, motivated me to keep trying, and in the space of about three

weeks I was able to do it. I think if I hadn't had that experience, I

would have given up trying to do it. And to me that is a model for one

aspect of what psychedelics can give you. It can give you a vision of

possibility, but then it doesn't show you anything about maintaining that

possibility. When the vision goes, the drug wears off, you are back where

you were, you haven't learned anything but you have seen that something is

possible. It is then up to you to figure out how to manifest the

possibility. I think that sense of anything is possible has enabled me to

accomplish a lot of things that I have done.

I will tell one story that I relate to that. I am in Arizona by the

weirdest of circumstances, my car broke down there twenty-five years ago.

It was an English Land Rover that I had driven to South America without

incident; I shipped it back. The moment I got it back in this country, it

was a liability. I couldn't get parts for it, I had had it overhauled at

that Land Rover Agency in Laguna Beach and got stuck there for five weeks

waiting for rings, and then I drove to Tucson. I was trying to get to

Oaxaca to deliver a baby of a friend of mine. The Land Rover Agency had

forgotten to pack one of the wheel bearings, which shattered, and it took

six weeks to get a wheel bearing. It was a February. A very warm, wet

winter, the desert was in full bloom; I never left. The baby got delivered

by itself, as they usually do. But anyway, I would have never, in my

wildest imagination, thought I would be living in the desert in Tucson,

Arizona.

ABOUT THREE YEARS AGO my best friend from medical school was named Chief

of Medicine at the University of Arizona by again, total stroke of fate.

He and our dean were a team at the University of Massachusetts, the two of

them had been instrumental in getting Jon Kabat-Zinn's program set up at

the University of Massachusetts. So when he arrived out in Arizona, he

said, "Well now that you have friends in high places, what do you want to

do?" I said, "Well, I would like to change all of medicine." And he said,

"Well, how do you want to do that," and I said, "here is what I would like

to do," and I outlined the basis of this program in Integrative Medicine,

which has now started and is in full swing. Our first doctor trainees are

on board and --this is big stuff--the whole school is behind it. It is, I

think, a model for medical education for the future and it is going to

happen all over the country. And by the way, when people hear about it, I

think the most common piece of feedback I get is people saying, "It's

about time." It is long overdue, you know, and it is about time, but, I

think if I didn't have that sense that anything is possible, I wouldn't

have attempted anything of that sort. But I always do, I just have this

sense of, "Why not?" and I think that comes directly from the

psychedelic vision.

Another aspect of the psychedelic vision for me that has been very

profound, is the sense that everything is alive or that at least, there is

no distinction between what we call living and non-living. That there is

some level on which everything is patterns of energy and that I have

perceived that energy. I remember being in a canyon in Arizona in a

psychedelic state and really being aware and able to see energy

circulating in my hand, which was resting on a rock and to see that the

energy in my hand was the same as the energy in the rock. That this was

the same stuff, that everything is composed of basically the same stuff,

which is in active movement. I think that sense has also led me to be very

open to techniques and ideas in medicine that many of my colleagues find

unable to fit in with their world views.

For instance, I have always been extremely interested in energy healing

and all of the touch techniques. You look at my friend who is Chief of

Medicine, Joe Alpert, a cardiologist; and he is a remarkably open person

to be in the position of Chief of Medicine. As I said, he was a good

friend of Jon Kabat-Zinn's and as a result of his association with our

Program, his horizons have been greatly widened. But he said to me the

other day, "You know you can talk to me about herbal medicine, I have no

problem with osteopathic manipulation or acupuncture, but don't talk to me

about homeopathy." He said, "I don't want to hear it," and this is the

attitude of many. I think of all of the alternatives out there, homeopathy

is probably the one that most pushes the buttons of the scientists,

because it is the one that really challenges the materialistic paradigm.

Here is a system of medicine based on giving people remedies that are so

dilute that there is little chance that the molecules are present and

Hahnemann, who invented this system said that he was liberating the

spiritual essence of the drug in this way. He wasn't interested in a drug

as a material substance, he was interested in it on the non-material

level. Whether you want to call that the energy of the drug or the

vibrational aspect of the drug or the spiritual aspect of the drug, you

can not use that language in talking to medical doctors and scientist. It

just enrages them.

FOR THAT REASON I have deliberately made homeopathy one of the required

subjects that we are teaching in the Program for Integrative Medicine. I

have done that very deliberately because I think it is interesting to see

what happens when you push all those buttons in an academic medical

center. But my reason for doing that is exactly from my direct

experience--from the psychedelic vision--of energy being the basis of

everything, that it is possible to approach the human body on an energetic

level and that may be a very valuable way of doing things. I want to see

what happens there, if you try to look at this in a scientific way or try

or are forced to develop a new conceptual paradigm to explain how

therapies can interact with the human body. I want to push that envelope

and see what happens.

I could go on in this vein but the main thing I want to leave you with is

that for me, the challenge has been to translate these experiences that

I've had in psychedelic states. I don't use psychedelics very frequently

anymore. It is really a period of experimentation that was in my past, but

my work is very actively derived from those experiences. It seems to me

that the challenge in our culture is not to have this vision over and over

again, it is really to see how the vision can be put into practice. How

can you implement it into this sphere of life in which you are involved

and produce change in that sphere, whatever it is. Mine happens to be

medicine and that has been a big one to take on, as you can imagine, but

for a variety of reasons it is very susceptible at the moment to being

moved in a big way. The reasons, by the way, on a material level, are

primarily economic.

Medicine is in enormous economic crisis today, it is really of its own

making. It set out on a course of being very uncritically involved with

technology and the dependence on technology is too expensive. At the same

time it is up against this enormous worldwide, social, psychological shift

among consumers who for a variety of reasons are moving toward natural

things. These combined economic forces are irresistible. Medical

institutions suddenly really have no choice but to move in this direction,

but it is amazing to watch it all happen so fast. At any rate, I am very

optimistic about the possibility for change there. That reminds me of one

other thing. I was interviewed very extensively in the past few months by

a New York Times reporter, who was publishing some long feature, she is a

woman in her mid-thirties who is a Harvard graduate, the daughter of two

Harvard psychiatrists, I liked her very much and she is very thoughtful,

very interesting and she wanted to read my whole body of work and asked

lots of questions. She started asking me about the drug stuff and I said,

"You really should read The Natural Mind first and then come back and talk

to me." So she started The Natural Mind and she called up and said that

she found it such a curious book; she said it seems so dated. I said,

"What do you mean by dated?" and she said, "Well, it just seems like it is

a product of another time." I said that, well, it was, but I said, "What

do you mean by that?" She said, "Well, it is so optimistic." As I began

talking to her about that actually I felt quite sad. She said that in her

peers, her generation, going through college... the sense that you could

change the world, is completely foreign to her, that it is so strange to

read. In a sense, this makes me feel very sad and yet again I think that

that optimism is something that for me derived from the psychedelic

vision. I don't know whether her generation has not had that, but if

younger people find that a dated view of reality, I feel very sorry for

them. I think my sense of optimism is very much confirmed by what I see

actually happening out there.

YOU KNOW, I really do think the world is changeable and that all this can

move quickly and astonishingly. I think also, even though change probably

builds on slow incremental movements, that when it becomes perceptible

sometimes the shifts are sudden. This is a popular view with Chaos

Theorists. To point out an example that I have seen used; if you have a

fish tank with fish and each day you are putting slightly more food in

than the fish can eat, without knowing that one day you come in and the

water is opaque and the fish are dead and floating on the surface. You

wonder how could that be, what happened, but what happened was the result

of very slow increments in which the flora was changed, the oxygen content

of the water was changed. When it reaches a flip point, then there is this

gross obvious change that seems to happen instantaneously. I think that is

the way social change happens and world change happens as well. So, I

think that doesn't spare you from doing the work day to day and putting it

into action but then I think the movements can be very dramatic and sudden

and amazing, so I remain extremely optimistic. And it just makes me very

sad if that is true of the generation younger than me. So, I will stop

there and let you comment.

C. Grob: Thank you, Andy. It's certainly good to have you here at a

meeting like this, talking about these issues. Clearly you are in the

public eye, as a spokesperson for the whole field of alternative medicine,

which is really having an enormous impact on how people are viewing health

and are viewing what they need to do to insure their own health. You are

certainly having an impact being right out there, center stage. What is

also quite extraordinary is looking at your own history and in a sense,

where your early vision was acquired. I think this is one of the

attributes of the psychedelics which often goes unacknowledged; the power

with which they endow individuals with a vision that often takes them

forward in their lives. Even individuals who haven't taken psychedelics in

years or in decades will often trace back pivotal decisions they have made

to those early experiences. I think it is really gratifying to see you,

particularly now in your position of prominence, very willing to speak of

such early experiences.

It is also quite fascinating to examine the medical profession in flux.

One of our institutions that seems to be so impervious to even the

slightest change, is now moving at a rapid rate. I wonder at what point

might our professions start to open up to the potentials that psychedelics

might have in terms of helping us understand health, understand illness

and understand new methods to intervene. Sometimes I, in my wildest of

optimistic visions, imagine a whole field of psychedelic medicine devoted

really to studying this phenomenon, a phenomenon that has gone virtually

ignored by Western medicine. But if you look back on the roots of our

healing structures, that which we inherited from our ancestors, we see

that much of early, very early so-called primitive medicine was on the

Shamanic healing model, which often used altered states acquired through

one method or another to facilitate healing; either through the healer

getting inside into the malady of the person and implementing energetic

changes, or the patient him or herself entering an altered space to

facilitate a process of healing. If we look to the future and anticipate

an evolution of our medical systems, might it be possible even to imagine

a role that psychedelics might play? Even a role that is accepted and

valued?

A. Weil: Actually that reminds me, I left out one very important component

of the psychedelic vision, which for me was the real experience that

external reality can be changed by changing internal reality. That is,

that by doing something in here, everything out there changes and I think

that has enormous relevance for medicine. I will give you another personal

experience. I think this was on a different occasion than that one I told

you about with the yoga experience, but it was again with LSD. I had had a

lifelong allergy to cats and didn't like cats. If I touched a cat and then

touched my face my eyes would itch and swell, and if a cat licked me I got

hives where they licked, so I always stayed away from cats. One day in an

LSD state, when I was feeling very centered, a cat jumped in my lap and I

just decided, well, I was going to enjoy the cat. So I played with the cat

extensively, I had no allergic reaction and I have never had one since.

That to me was a very powerful experience, how something that I thought

was a lifelong pattern could change in an instant as a result of a change

in internal reality.

I have one other to contribute, this one I have not written about but it

is even more impressive. I had very fair skin as a child and was always

told I couldn't get tan. We used to go down to the Jersey beaches in the

summer and I remember endless sunburns with sheets of skin peeling off,

this was in the days by the way, when what we used for suntan lotion were

products that probably magnified the sun reaching your skin. But this is

something I just accepted about myself; that I couldn't get tan, that my

skin would peel and that was always my experience. At this same period in

1970 when I was making all these changes in my life; I decided that this

is something that has got to change. I remember, again with psychedelics,

for the first time I lay naked in the sun and exposed my whole body to

sun, and lo and behold, my skin got tan for the first time in my life and

it has ever since.

Those three have been very remarkable experiences: the sense of anything

is possible, that there are no limits, at least in the ideal world, and

that the key to changing external reality and reactions to the environment

lies in internal transformations. When I work with patients, especially

patients who have chronic pain or chronic illnesses, even though I may not

know how to do it, I think it is important to give them a sense that this

is changeable and that they should keep experimenting. My general sense is

that the real change is at the level of consciousness. If these tools were

available to us as practitioners, I could see a lot of potential uses

there and not just in psychiatric medicine, which is where it has been

talked about the most, but especially in physical medicine.

I think you could take people with severe allergies, for example, and give

them a series of experiences with decreasing doses of the drug to teach

them how to unlearn an allergy and maybe in similar ways you could teach

people how to unlearn chronic pain or to unlearn musculoskeletal problems

or digestive problems. I could see great potential use for it.

C. Grob: I think it's good to hold this concept that anything is possible,

a sense that even structures that we feel are too resistant to change, can

change. To hold an optimistic vision of what may be possible. I think we

are beginning to see examples that the realization may be more accessible

than we had thought. For example, no one really anticipated the collapse

of Eastern Europe, the way it happened with such rapidity and in such an

overwhelming manner. I think we are going to see in medicine simply more

receptivity. The public at large wants alternative perspectives,

alternative approaches, the very notion of putting forward a program for

training practitioners in alternative medicine at a prestigious medical

school, ten years ago, would have been unheard of. That would have been a

pipe dream of the widest magnitude and here it's already starting to

happen. So, I think in a sense what we need are visions such as this and a

sense of surety that with time and persistence change is feasible. I think

this is really a powerful example for us to hold and also for us to carry

with us as we take the visions that we have for the future, but also with

realization that change is possible. I don't know, Dennis, do you have

some comments here?

D. McKenna (pictured at right): Yes I do, I think that Andy makes the good point, that

psychedelics can be important in individuals' lives in terms of orienting

them to a wider vision or be an influence in terms of directing people. I

think psychedelics ultimately are something that you come to as an

individual. The challenge that we face is trying to relate our own

individual experience and its influence in our own lives to the greater

society, and ultimately beyond society to our species' fate. This is where

the challenge lies, trying to reconcile these two, because the way that at

least our western society is structured, there are no paradigms for

joining these two. In fact, societies seem mostly set up to discourage

this kind of self discovery and to repress it by legislative means if

necessary, but by whatever means. It is not something that is encouraged.

I think that one of the biggest challenges for the next millennium is, how

are we going to take our own individualistic psychedelic visions or

inspirations and try to diffuse those into a larger society. This is

always the problem. As Andy has said earlier, now that you have the

vision, what do you do with it and how do you somehow give expression to

it in the way you live and the way that society operates.I think that is

really the challenge. I am optimistic too, it must be that optimism is

infectious because I think there are a lot of discouraging things going on

but overall I think that trends are in the right direction.

D. McKenna (pictured at right): Yes I do, I think that Andy makes the good point, that

psychedelics can be important in individuals' lives in terms of orienting

them to a wider vision or be an influence in terms of directing people. I

think psychedelics ultimately are something that you come to as an

individual. The challenge that we face is trying to relate our own

individual experience and its influence in our own lives to the greater

society, and ultimately beyond society to our species' fate. This is where

the challenge lies, trying to reconcile these two, because the way that at

least our western society is structured, there are no paradigms for

joining these two. In fact, societies seem mostly set up to discourage

this kind of self discovery and to repress it by legislative means if

necessary, but by whatever means. It is not something that is encouraged.

I think that one of the biggest challenges for the next millennium is, how

are we going to take our own individualistic psychedelic visions or

inspirations and try to diffuse those into a larger society. This is

always the problem. As Andy has said earlier, now that you have the

vision, what do you do with it and how do you somehow give expression to

it in the way you live and the way that society operates.I think that is

really the challenge. I am optimistic too, it must be that optimism is

infectious because I think there are a lot of discouraging things going on

but overall I think that trends are in the right direction.

C. Grob: We have time for questions or comments for Andy.

L. Huxley: I would like to say one thing. Andy has given me, I think all

of us, a great hope that one of these visionary common sense ideas might

become true one of these days. I think that in a conscious society, a

great doctor would say to his patient, look here, I am going to try to do

my best for you but I can do very little. But I have one little bit of

news, you can do a lot for yourself. Maybe that is going to happen because

of you.

Audience question: Dr. Weil, here is another element of how psychedelics

might be helpful in our health; I know there are a lot of things going on

in my body I am not aware of, and perhaps some things which need

attention. Perhaps there is cholesterol building up, or perhaps I am

keeping muscle tension in certain places, or perhaps my insulin is off, so

I am not aware of these things. We have these marvelous plants that help

to increase our awareness, are there particular techniques or particular

plants that might help us become more aware of what is going on in our

bodies and where our attention may need to be focused?

A. Weil: Well first of all, I don't think you need to become aware of too

much of what is going on in your body. I think it is good to assume that

your unconscious mind is running things just fine. I think you could make

yourself very crazy by becoming too aware of what is going on. Think if

you had to consciously run all the things in your body, that would be a

nightmare. However, it is clear that in some people that come for medical

attention, the problem has been that they have ignored things that they

should have paid attention to. In most cases, that is not even visionary

common sense, it is just basic old common sense. Runners that run in spite

increasing pain in their knees, for example, are just ignoring simple

common sense. So I think in the general public there is a kind of basic

body awareness that people should know about. I am committed to bringing

that kind of information to kids because I think we don't do a very good

job about giving children preventive health information and I think the

principles are very simple and I am not so sure we need psychedelic tools

to do that. I think that is just basic common sense. I have a wonderful

collection of anecdotes of people who, using psychedelics, have become

aware of information from their body that was very useful to them.

Absolutely, I have seen that over and over, that has helped guide them in

choices that they have made in knowing that there was something wrong with

their body or something was not wrong with their body. So I think they

certainly can function that way and again I can see a potential use for

them.

D. McKenna: I would like to ask Andy, coming off your question, do you see

psychedelics as a potential diagnostic tool for physicians, being used

much in the same way that ayahuasca for instance, would be in tradition

settings?

A. Weil: That's a very interesting question. We have twelve core subjects

in the Integrative Medicine Program that the physicians are learning and

we have recruited faculty of the whole University of Arizona as well as

outside to develop these courses. One of the courses is called The Art of

Medicine and this is all material that is not usually taught in medical

schools; one aspect of this is intuition. I have always maintained that

all diagnosis was based on intuition and that all of the great

diagnosticians that I have met have been highly intuitive, although they

may not have recognized that themselves. I think that the diagnostic tests

that we do can be used to confirm or discard hunches that you form

intuitively. But a problem in our educational system is that not only is

intuition not rewarded, actually students are actively penalized for using

intuition and not relying on objective data. And that has gotten even

worse with the whole medical malpractice situation because now, with the

great fear of litigation, there is more and more emphasis on not doing

anything unless you have objective numerical data to support what you do.

So, I am very much interested in how you train intuition in people and I

could imagine a future world in which psychedelics were available for

that, they could be used in a way to become more aware. Everybody is

intuitive, but most of us aren't trained to pay attention to it or to act

on it and I think that is the challenge. I could definitely see drugs

being used in that way.

Audience question: Your talk made me think about three different kinds of

people or three different kinds of situations, I am not quite sure how to

say it but, there are people who have taken psychedelics early in their

lives or careers and kicked the visions into their lives, there are people

who are involved in spiritual practices in which the use of psychedelics

is an ongoing thing and there are people who take psychedelics over and

over again and don't seem to do very much into bringing it into their

lives. Have you thought about what accounts for the differences among

those three kinds of people?

A. Weil: I haven't. I will add, by the way, a fourth category, which is

people who have had the vision without ever using psychedelics. And they

can either take it into their lives or not, as well. No, I haven't thought

about that, I don't know. I don't know what accounts for that.

Audience question: My comment might be a good follow up to that. My

experience started with spontaneous visions as a teenager and then into

meditation and then occasional use of psychedelics and then a lot more

meditation, long retreats which seemed to duplicate the psychedelic

experience through natural meditative practices. And then, going into

medicine and psychiatry and now six years of psychoanalytic training. I

think the basic ego strength of the user before the psychedelic experience

or the spontaneous ego experience is a big factor in whether you bring

this vision into the world or not. We are getting into the realm of

psychiatry and a lot of these issues may have to be dealt with, with a

dialogue between internal medicine and psychiatry as well as alternative

medicine. In many ways psychiatry may be behind the boat, but it may be

the future of how we integrate. How do we bring forth the natural healing

abilities of the unconscious mind into our personal lives and bring out

those visions that are within us into manifestation in helping the world

with its problems?

A. Weil: That makes me think of several things; first is that the first

time that I took mescaline in my freshman year, I really had minimal

experience because I think I had so much anxiety about it. I took it again

about a month later and had what certainly felt to me like a mystical

experience and it was very overwhelming. But I think when I came out of

it, some part of me knew that if I followed through with the implications

of it I was not going to go through college and medical school. I kind of

shut that all off and it wasn't until I was probably out of medical

school, beginning to do an internship, that I began to experiment with

psychedelics again and recover that. I think if at that point I would have

pursued a psychedelic career I would have not gotten my medical degree and

not done what I now do. So that makes me somewhat cautious about young

people and that is one thing that I might tell young people; there may be

an appropriate time in life to do this and that maybe it is worth waiting

a certain period.

I CAN'T IMAGINE WHAT would have happened to me if I would have discovered

these drugs when I was in high school, for example. Another thought that I

have is to what you said about psychiatry and medicine; I think this is

one of the great tragedies of modern medicine and is really part of the

legacy of Descartes. There are people who say that if western civilization

took one wrong turn, it was with Descartes; certainly the split between

psychiatry and medicine is in that Cartesian tradition. I think it is very

unfortunate. I am doing what I can to repair that. I was asked to give

psychiatry grand rounds at the University of Arizona a few months ago and

to my delight, they were very unhappy that they had been left out of the

Integrative Medicine Program and wanted to know how they could

participate. So, I have definitely opened a dialogue with the psychiatry

department. Even if they just want to get in on a level of doing research,

that is fine. I would like to involve them much more. The concept behind

psychiatry--the word means soul doctoring--I can't imagine anything more

important, especially if you feel as I do, that much if not all of disease

originates on the nonphysical level and then eventually manifests on the

physical level. And yet, it is so ironic that of all of the medical

specialties, psychiatry is the one that is most mired in materialism and

sees all disorders of consciousness as being the result of brain

biochemistry, when it could just as well be the other way around. And that

all therapy is giving people drugs and if a psychiatrist is treating a

person who develops a physical problem they are referred to an internist

and if an internist has a patient who is believed to have an emotional

problem, they are referred to a psychiatrist and there is no conversation

there. That is a big problem, it is something very wrong with medicine

today, and something that we are trying to fix.

Audience question: I would like to follow up on that, being a

psychiatrist. I really like your thing about, "Anything is possible."

Another dichotomy that I see, that worries me, and that it is often

expressed in a psychedelic group, is the dichotomy between western

medicine and alternative medicine. I liked your concept of Integrative

Medicine rather than the idea that "If you take Prozac you are bad; if you

take St. John's Wort-- which is a herb but it is medication--you are

good."

A. Weil: I get concerned about that kind of dichotomy, so the whole thing

of, "Anything is possible and everything should be integrated," is another

area that I don't see very many people addressing. Let me expand that even

more. To generalize, the basic problem is the either/or model. And again,

this is something that I relate to a psychedelic experience. I remember an

even earlier acid experience in Death Valley. It was one night on a full

moon in June, so it was blazing hot in the day, but during the hours that

I was on LSD I couldn't tell whether I was warm or cold at night. I felt

both sensations simultaneously, and to me that experience of ambivalence,

of paradox is something that has been very much alive for me in

psychedelic experience. It has always led me to approach things from a

both/and formulation rather that either/or formulation. And I think that

whenever you run up against either/or formulations, you should try to

replace it with both/and.

Audience question: I first read The Natural Mind when I was in my first

year of medical school and that was my first exposure that there was

something called alternative medicine, which you discussed as a sort of

natural outcome of a psychedelic world view. I find that book to still be

perhaps the most cogent, conducive, intelligent discussion of drugs and

their role in society that I have ever read. At the time that you wrote

that you were fairly unknown and I don't think very many people have read

it. Now that you have found a large audience, I would like that book to

find a large audience and would like to see a revised version, written to

reach out to the public. At the same time, I see that might really

jeopardize what you are trying to do-- bringing alternative medicine into

the fold--so that is a paradox but I just wanted to put out that I would

like to see more people find that book without it somehow endangering your

status of bringing alternative medicine into the mainstream.

C. Grob: We can take one more question or statement before the break.

Audience question: I would like you to elaborate a little bit more on an

either/or, both/and issue that I face. I am a psychiatrist and I work with

oncology patients and the question is, on the one hand there are a lots of

alternatives and things that people can do to get better, but on the other

hand you speak very cogently about the dangers of guilt and responsibility

for getting better. The biological power of illness is so great that

sometimes patients come to me and they are overwhelmed with possibilities.

They shout, "What should I do? I am not meditating well enough, I am not

doing enough imagery, etc." How do I help them to get to a both/and model?

A. Weil: In Spontaneous Healing I have a chapter called Cancer as a

Special Case, and I really find it useful for a lot of reasons to separate

cancer out from other sorts of diseases. It is the one in which the

polarization between conventional and alternative medicine is most

intense. I think cancer is different in that, by the time we diagnose it,

it is a condition of very long standing, in which the body's healing

mechanisms have failed. So you are up against a different order of

magnitude of difficulty than in moving other kinds of diseases. There have

been so many New Age books about cancer, talking about the mind-body

connection. Frankly, I am very skeptical of a lot of that. My sense is

that cancer mostly results from very complex interactions between genes

and environment, in which the role of emotions and belief is obscure. I

can see how states of grief or depression could suppress immunity and

allow a preexisting cancerous tumor to grow faster, but I personally don't

think that mental factors have a great deal to do with the origin of

cancer. That is my own belief. I think in working with cancer patients, it

is very appropriate to tell them that their mental states have a role in

their general health and can specifically affect immunity, and to give

them techniques like visualization that can help with that, but I think

one has to be very careful about feeding into that idea, "You gave

yourself cancer." I told a story in Spontaneous Healing, that I will just

repeat that I think is very revealing.

I have always liked asking patients why they think they got sick, and I am

interested in how people formulate that to themselves. When I was a

medical student, this was in the late Sixties, I asked a lot of women who

had breast cancer--and these were women of my grandmother's

generation--why they thought they got breast cancer. Everyone, one hundred

percent, said that they got it because they had a past injury. The

typical formulation was, "Thirty years ago, I fell against the kitchen

table and hit my breast," or "I was in a car accident and my breast got

hurt." We know of no connection of trauma and breast cancer, but that was

how women in that generation explained breast cancer to themselves.

WHEN I ASK WOMEN TODAY with breast cancer why they got breast cancer,

nobody ever mentions injury. Now all I hear is formulations like, "For all

those years I bottled up my feelings," or "I never expressed the rage I

felt towards my husband." Now, I don't think we have any greater evidence

that breast cancer results from bottled up feelings than from past trauma,

but this represents an enormous social shift in this culture in how women

explain breast cancer. And there is a big difference here, because if you

think you got breast cancer because you fell against the kitchen table,

that is an act of God, it is an accident. If you think you got breast

cancer because you bottled up your feelings, it is your fault. It is

failure on your part. That has very different implications for how you

think about yourself. And personally, I am very uneasy about the amount of

popular literature that feeds into those formulations today, about cancer.

That is all I can tell you. I think it is a very careful line that you

have to walk, and I think the thing that you want to focus on is telling

people that their states of mind probably influence their immunity and

their level of general health, so it is worth trying to work on that

through whatever techniques we can offer them, but that there is no point

in looking for how that fed into the origin of the illness.

Next Article

|