The New York Times

January 20, 2005

Décor by Timothy Leary

by Mark Allen

At first glance it looked like something in the window of a TriBeCa furniture store, an oversize lamp from the early 60’s maybe. But when Kate Chapman flicked a switch and the three-foot high latticework cylinder in front of me began to spin, it was clear that we were dealing with more than just another piece of midcentury flotsam.

SITTING, STARING, TRIPPING Kate Chapman, an artist in Brooklyn, embarks on an inner voyage with her Dreamachine.

SITTING, STARING, TRIPPING Kate Chapman, an artist in Brooklyn, embarks on an inner voyage with her Dreamachine.

The machine started to cast strobelike patterns of bright light on our faces, and when I closed my eyes as instructed, there they were, the dazzling multicolored forms that I’d been told about: mandalas and crosses and even Mandelbrot fractals, dancing across my eyelids.

I was sitting on the floor of Ms. Chapman’s Brooklyn loft, and she was demonstrating her prized household appliance, a 1996 Dreamachine originally made for William S. Burroughs. Besides the trippy visual effects the device is said to induce an “alpha state” – a state conducive to lucid dreaming or intense daydreaming – in people who face the cylinder with their eyes closed as it spins around a bright light.

Dreamachine enthusiasts – whose ranks have swelled recently thanks to chat forums and a book published last year – claim that it promotes a trancelike serenity, intensifies creativity and insight and even uncovers suppressed memories. Ms. Chapman’s Dreamachine is one of more than a thousand that have been manufactured since the early 90’s by a California composer and conductor named David Woodard. One is on display this month at the Clair Obscur Gallery in Los Angeles along with an exhibit of photographs of Burroughs taken by John Aes-Nihil, an underground filmmaker, and the premiere at the gallery of his film, “William Burroughs in the Dreamachine.” Burroughs, along with other figures from the Beat Generation like Allen Ginsberg and Timothy Leary, was fascinated, even at times obsessed by the Dreamachine, which was invented in 1959 by their fellow Beats Brion Gysin, an artist, and Ian Sommerville, a math student at Cambridge. Mr. Leary called it “the most sophisticated neurophenomenological device ever designed”; Mr. Burroughs experimented with it for nearly four decades. (The film shows him using his Dreamachines at his home in Lawrence, Kan., shortly before his death in 1997).

I had come to Ms. Chapman’s loft to see if the machine lived up to the hype, but I didn’t get very far in my first session. The colorful undulating patterns that I began to see almost at once were intriguing: far more vivid than the fuzzy images you see when you rub your eyes, although just as hard to focus on. But as far as I could tell my state of consciousness barely changed during the 20 minutes that I sat cross-legged in front of the spinning cylinder. When I opened my eyes, Ms. Chapman seemed to sense my disappointment.

I had been somewhat skeptical, but was still hoping for more, given what I had learned about the machine and its history. Mr. Gysin and Mr. Sommerville built the first Dreamachine after learning of research by John Smythies and W. Grey Walter, scientists who had noted in experiments that light flickering at 8 to 12 flashes a second against a subject’s closed eyelids seemed to slow the electrical pulse rate of the subject’s brain to a state of semiconsciousness known as the alpha state and produce rich dreamlike imagery.

Although his fellow Beats were excited about using the device, Mr. Gysin had broader ambitions for it and tried to distance himself from their enthusiasm, says John Geiger, the author of “Chapel of Extreme Experience: a Short History of Stroboscopic Light and the Dream Machine” (Soft Skull Press, 2004).

“He was focused on its commercial potential,” Mr. Geiger said. “He imagined a Dreamachine in every suburban home, in the spot formerly occupied by the television set, but broadcasting inner programming. He really saw this idea as his ticket out of bohemia town.”

Mr. Gysin’s attempts to commercialize the Dreamachine during the 60’s and 70’s never got very far. He met with corporations like Philips, Columbia Records and Random House, but they did not share his vision of the Dreamachine as the successor to TV. They were also worried about lawsuits resulting from seizures caused by the machine

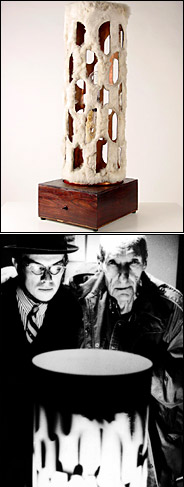

ALPHA-STATE MALES William F. Burroughs, left, examines a Dreamachine with its maker, David Woodard, in 1997. Two years later Mr. Woodard made a version covered in ermine fur, top, for Burroughs’ memorial service.

“For the high majority of people this is a completely safe device,” Mr. Geiger said. But Dr. Robert Fisher, the director of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at Stanford, said that 1 in 10,000 people is likely to have a seizure in reaction to the its stroboscopic light, and that children are about twice as susceptible.

David Woodard, who now makes Dreamachines to order at his studio in Los Angeles, learned about the device from a friend of Mr. Gysin’s a few years after his death in 1986. Mr. Woodard was able to borrow the original Dreamachine templates from the friend, and built his first one in 1989; within a few years word of mouth and modest advertising led to a full-fledged business. He made two for William Burroughs and has made others for celebrities including Iggy Pop, Beck and Kurt Cobain. ( Rumors circulated that Cobain had been using the device heavily in the days leading up to his suicide, although later reports contradicted this.)

Mr. Woodard charges $500 for a basic model with a cylinder of acid-free matting board. (The cylinder surrounds a 150-watt bulb, which is mounted in the center of a wood base holding a motor that spins the cylinder at 80 r.p.m.) Custom models, with cylinders made from steel, copper or cocobolo wood – or even covered in ermine fur – can cost as much as $3,000.

After the mixed success of my first experiment with the Dreamachine, my hostess urged me to try again. Ms. Chapman, 30, is a former neuroscience researcher for the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, a nonprofit organization that sponsors “scientific research designed to develop psychedelics and marijuana into F.D.A.-approved prescription medicines,” according to its Web site.

“I’m just an artist now,” she said.

Ms. Chapman thought it might be helpful if my body were more relaxed, so I lay down on a sofa, and she put on soothing music. She flicked the machine back on as I shut my eyes. A moment later there they were, the same flashing patterns as before. After a while I became bored and my mind began to drift.

That’s when it happened. I didn’t “see” as much as I strongly imagined a campfire in a clearing in a dense forest at night. My boyfriend Jim was sitting to my left, laughing. Later I seemed to find myself in a large empty auditorium, walking toward some chairs arranged in the middle of the room. In one creepy moment I was in a basement hallway, following closely behind someone walking ahead of me, whose face I couldn’t see.

I was imagining these scenes so vividly that it was almost as if I were seeing them. The thoughts had a kind of slow-motion jump-cut feel, just like dreams, but because I was fully conscious, I was able to contemplate all of this as it was happening.

With my eyes still shut and my mind now very relaxed and slightly adrift, I started to notice that the wall of flashing patterns was receding backward and developing a dark border around its edges. It was at that moment that I sensed someone to my left, sitting beside me, watching what I was watching. This figure was not in the room with me, but in my head, which had now turned into a little theater. I felt that if I turned my head, I would be able to look over at this person.

I opened my eyes, and reality rushed back in, to my relief. That last

vision hadn’t really been frightening, but it wasn’t exactly heartwarming either. But I was impressed. As I talked to Ms. Chapman about my experience, I became aware of an unusual serenity and mental clarity, as if I had just waked from a refreshing nap.

Days after my experience with Ms. Chapman I found myself craving the Dreamachine and the vivid imagery and sense of calm it had produced. I’m not sure I would part with $500 to bring one into my life. But having lived through the experience, it was hard not to think about Mr. Gysin’s vision of an alternate-universe America in which every home would tune into internal landscapes instead of commercial programming.

The New York Times published an article about dream machines that featured Kate Chapman, described in the article as “a former neuroscience researcher for the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies.” Kate worked on a rat MDMA neurotoxicity study funded by MAPS as well as on the Janiger follow-up study.